Stored DOM XSS

This writeup delves into the 13th XSS lab in port swigger.

Introduction

This lab tackles a stored DOM-XSS vulnerability. Let’s try to find it.

Investigation

We have the usual setup: a blog with posts and the ability to view individual posts, but in this case, there is no search bar.

Since we are dealing with stored DOM-XSS, the payload must be stored persistently somewhere in the website—either in localStorage, a database, etc.

So let’s check something persistent. The persistent input we can enter here is… you guessed it: a comment.

When viewing a specific post, we are able to leave a comment on that post.

Instead of immediately trying our classic payload like <script>alert(1)</script>, it’s better to first inspect the source code and understand how comments are handled.

Checking Source Code and Crafting the Payload

While inspecting the page source, we find the following scripts:

1

2

<script src='/resources/js/loadCommentsWithVulnerableEscapeHtml.js'></script>

<script>loadComments('/post/comment')</script>

Let’s take a look at the loadCommentsWithVulnerableEscapeHtml.js file.

After reviewing the source code, we see the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

function loadComments(postCommentPath) {

let xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.onreadystatechange = function() {

if (this.readyState == 4 && this.status == 200) {

let comments = JSON.parse(this.responseText);

displayComments(comments);

}

};

xhr.open("GET", postCommentPath + window.location.search);

xhr.send();

function escapeHTML(html) {

return html.replace('<', '<').replace('>', '>');

}

function displayComments(comments) {

let userComments = document.getElementById("user-comments");

for (let i = 0; i < comments.length; ++i)

{

comment = comments[i];

let commentSection = document.createElement("section");

commentSection.setAttribute("class", "comment");

let firstPElement = document.createElement("p");

let avatarImgElement = document.createElement("img");

avatarImgElement.setAttribute("class", "avatar");

avatarImgElement.setAttribute("src", comment.avatar ? escapeHTML(comment.avatar) : "/resources/images/avatarDefault.svg");

if (comment.author) {

if (comment.website) {

let websiteElement = document.createElement("a");

websiteElement.setAttribute("id", "author");

websiteElement.setAttribute("href", comment.website);

firstPElement.appendChild(websiteElement)

}

let newInnerHtml = firstPElement.innerHTML + escapeHTML(comment.author)

firstPElement.innerHTML = newInnerHtml

}

if (comment.date) {

let dateObj = new Date(comment.date)

let month = '' + (dateObj.getMonth() + 1);

let day = '' + dateObj.getDate();

let year = dateObj.getFullYear();

if (month.length < 2)

month = '0' + month;

if (day.length < 2)

day = '0' + day;

dateStr = [day, month, year].join('-');

let newInnerHtml = firstPElement.innerHTML + " | " + dateStr

firstPElement.innerHTML = newInnerHtml

}

firstPElement.appendChild(avatarImgElement);

commentSection.appendChild(firstPElement);

if (comment.body) {

let commentBodyPElement = document.createElement("p");

commentBodyPElement.innerHTML = escapeHTML(comment.body);

commentSection.appendChild(commentBodyPElement);

}

commentSection.appendChild(document.createElement("p"));

userComments.appendChild(commentSection);

}

}

};

We immediately notice that the escapeHTML function uses a vulnerable sanitization technique. It relies on the .replace() method to escape < and >, but .replace() only replaces the first occurrence, not all occurrences.

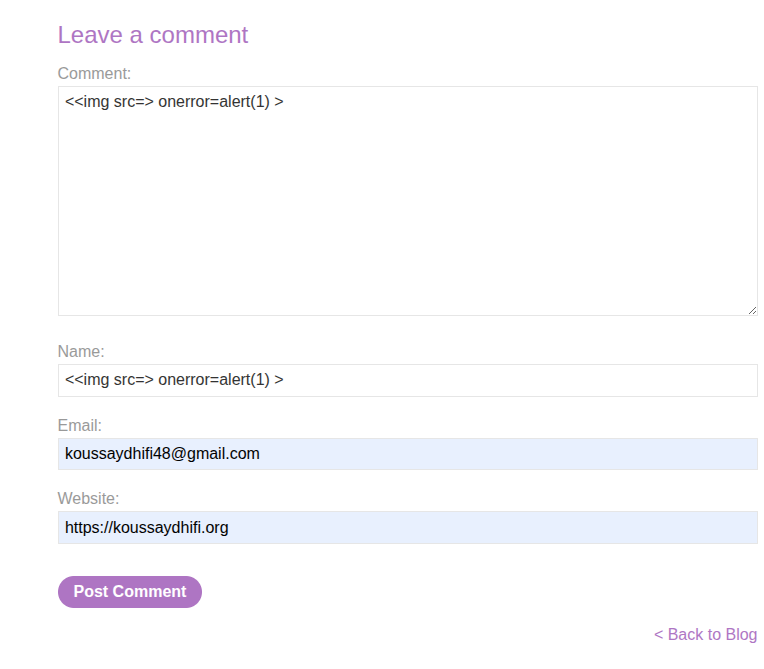

This means we can craft a payload such as:

1

<<img src=> onerror=alert(1) >

What happens internally is:

- The first

<is replaced with< - The first

>(insidesrc=>) is replaced with> - The final

>remains untouched

As a result, the payload becomes:

1

<<img src=> onerror=alert(1) >

This is still interpreted by the browser as valid HTML, allowing the onerror handler to execute.

We can inject this payload into either the author field or the comment body, since both use the same vulnerable escapeHTML function.

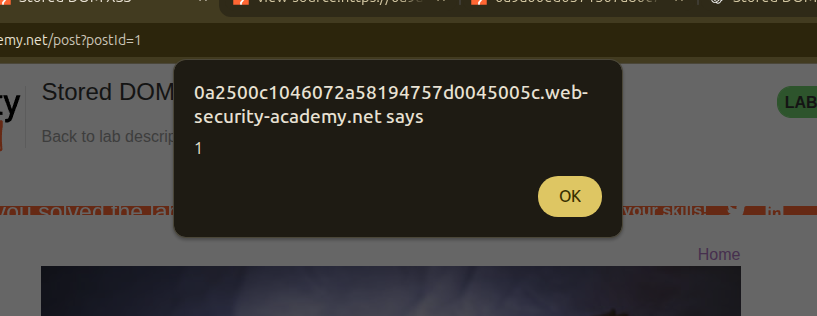

And… boom 💥 — we get the alert exactly as expected.

Conclusion

This was a great lab. I learned how stored DOM-XSS works: stored user input is later rendered into the DOM using JavaScript, and improper client-side sanitization leads to code execution.

A small mistake in escaping logic can be enough to introduce a serious vulnerability.